October 14, 2014

#research

Update: I titled my first book after its central characters, adopting a contemporary term for these new specialists — “the computer boys” — that for me neatly captured mixed sense of awe, mystery, suspicion, and derision with which this unexpected powerful new group of experts were regarded by their contemporaries. Like the other terms collectively applied to these experts (“wizards,” “hackers,” “gurus,” and “cowboys”) the term “computer boys” spoke to the ways in which these specialists were alternatively admired for their technical prowess and despised for their eccentric mannerisms and the disruptive potential of the technologies they developed. To many observers in this period , it seemed the “computer boys” were taking over, not just in the corporate setting, but also in government, politics, and society in general.

But there is another, more literal sense in which “the computer boys took over,” and has to do with the masculinization of computer culture that occurred over the course of the late 1950s and 1960s. It often surprises people to learn that computer programming was originally envisioned as women’s work, and that it took several decades for computing to acquire its distinctively masculine identity.

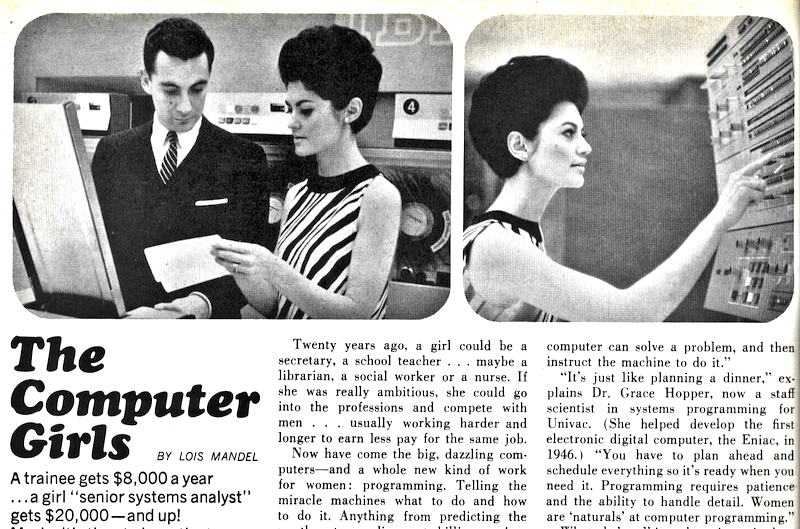

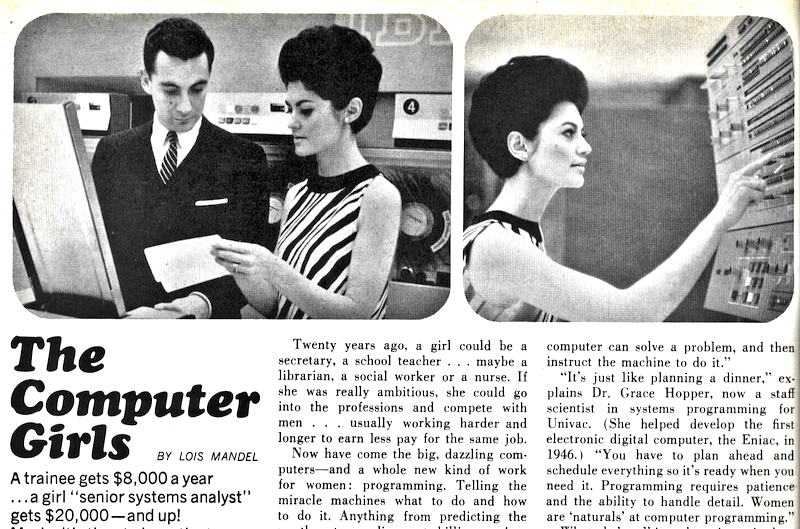

In both the Computer Boys book and a subsequent essay in the edited volume Gender Codes (which focused on the astonishing 1967 Cosmopolitan Magazine Computer Girls article pictured above) I wrote about the remarkable occupational sex-change that occurred in the history of the computer professions. I focused particularly on the ways in which the widespread use of aptitude testing and personality profiles in hiring practices in this period helped create and reinforce the stereotype of the computer programmer as young, male, and anti-social.

I now in the process of extending my history of gender and computing to cover the period between the late 1960s and early 1980s. I have a new article coming out in the forthcoming special issue of Osiris dedicated to scientific masculinities. The article is called ‘Beards, Sandals, and Other Signs of Rugged Individualism’: Masculine Culture within the Computing Professions. The focus of this piece is on the emergence of the “computer bum” in academic computer labs in the late 1970s and its subsequent popularization of this almost exclusively male phenomenon in the sensationalist media coverage of the “computer hacker” in the early 1980s.

Update: the published Osiris version of the Beards and Sandals paper is now available.

But while this new piece focuses processes of masculinization, the underlying assumption is, of course, that there is a larger history of women in computing against which these processes are revealed. It is too early to reveal much about the forthcoming Osiris paper, but in honor of Ada Lovelace day, here is one of my favorite lines from the new work:

… to borrow a relevant metaphor from computer programming itself, the presence of women in early computing was a feature, not a bug.

It is very exciting how much to see how much is happening in the history of computing in celebration of this day (and in anticipation of future celebrations), from historical documentaries on the ENIAC programmers and Grace Hopper to events aimed at encouraging women in computing.

September 20, 2014

#research

#media

For the upcoming MICE (Mistakes, Ignorance, Contingency, and Error) Conference in Munich I have prepared a paper entitled “When Good Software Goes Bad: The Surprising Durability of an Ephemeral Technology.”

In theory, software is a technology that cannot be broken. Virtual gears do not require lubrication, and digital constructs never fall apart. Once a software-based system is working properly, it should continue to work in perpetuity — or at least as long as the underlying hardware platform it runs on remains intact. Any latent “bugs” that subsequently revealed in the software system are considered flaws in the original design or implementation, not the result of the wear-and-tear of daily use, and ideally could be completely eliminated by rigorous development and testing methods.

In practice, however, most software systems are in constant need of repair. Beginning in the early 1960s, large-scale computer users discovered, much to their surprise, that between 50% and 70% of all their operating expenditures were being devoted to “software maintenance.” This meant that most computer programmers were (and are) spending most of their time “fixing” other people’s computer code.

You can read a draft version of the paper here.

May 12, 2014

#research

The Rob Kling Center for Social Informatics has awarded me a Research Fellows Grant for the academic year 2014-2015. This grant will be used to fund research on my global environmental history of computing.

March 21, 2014

#research

At the heart of the discipline of computer security is the problem of risk: how to analyze and quantify risks that are for the most part invisible, intangible, and not immediately life-threatening; how to communicate risk to computer users, software developers, and policy-makers; and how to balance the costs associated with alleviating risk against other considerations such as ease-of-use, access, accessibility, and profitability.

Although there is a large technical literature on risk in computer security, the principle focus of this literature is on the psychology of individual risk evaluation or on techniques for communicating risk to the public. But there is a large literature coming out of the history of science and technology that deals with the broader construction of risk as a social and historical phenomenon.

As part of the forthcoming workshop on Computer Security History hosted by the Charles Babbage Center, I am developing a paper that situates the computer security in the larger context of what Anthony Giddens famously called “manufactured risk.” The goal of this project is to mobilize the social and cultural history of “computer hacking” and “cybercrime” (focused primarily on the period in the early- to mid-1980s when these phenomena for the first time received widespread media exposure) to inform contemporary strategies for engaging with risk in the context of cybersecurity.

The paper is called From Whiz Kids to Cybercriminals: Emerging Narratives of Risk in Computer Security

February 20, 2014

#teaching

#research

I am very pleased to announce that I have been appointed an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science. I am thrilled to be part of this lively and accomplished group of scholars!

December 06, 2013

#teaching

New Course We are often told that we are living in an “Information Society,” and indeed, this is a truth that seems self-evident: communications and information technologies increasingly pervade our homes, our workplaces, our schools, even our own bodies. But what exactly do we mean when we talk about the “Information Society”? If we are living in an Information Society, when did it come into being? What developments — social, economic, political, or technological — made it possible? How does it differ from earlier eras? And finally, and most significantly: what does it all mean?

For the Spring 2014 semester, I am introducing a new course: I222: The Information Society. This course was specifically designed to provide students from a wide variety of humanistic or social scientific disciplines the tools that they need to make sense of the relationship between social and technological change. I222 fulfills the Social and Historical Studies requirements of the Indiana University General Education Requirement.

This course will explore the ways in Western, industrialized societies, over the course of the previous two centuries, came to see information as a crucial commercial, scientific, organizational, political, and commercial asset. Although at the center of our story will be the development of new information technologies — from printing press to telephone to computer to Internet — our focus will not be on machines, but on people, and on the ways in which average individuals contributed to, made sense of, and come to terms with, the many social, technological, and political developments that have shaped the contours of our modern Information Society. Our goal is to use these historical perspectives to inform our discussions about issues of contemporary concern about information technology.

You can find more information about the course at i222info.org.

November 05, 2013

#media

It has been a busy month of conferences and speaking engagements.

The Commission for the History and Philosophy of Computing hosted the second in a series of HAPOC conferences in Paris this year. This was an extraordinarily full and productive conference, with speakers and participants from all over Europe, the UK, and the United States. My contribution was a talk on “the multiple meanings of flowcharts.”

The Society for the History of Technology conference in Portland, Maine, featured many papers in computing related issues. The Special Interest Group on Computing and Information Science (SIGCIS) hosted a day of talks devoted entirely to the history of computing. My SHOT talk was devoted to exploring what I am calling “the environmental history of computing.”

Finally, I attended for the first time the annual conference of the Association for Internet Researchers in Denver, Colorado. Our panel was organized around the idea of revisiting some of the canonical works in our respective disciplines (history, anthropology, communications) in light of changes in information technology. I spoke about the classic Latour/Woolgar ethnography of science Laboratory Life and asked, in reference to the study of contemporary, computer-centric scientific practices, What Would Bruno Do?.

August 18, 2013

#media

This week the National Academy of Sciences is celebrating its 150th anniversary with a Sackler Colloquium called “Celebrating Service to the Nation.” Among other things, they are hosting a series of speakers and panels discussing various aspects of NAS history.

At 1:20 PM EST on Friday, October 18, I will be talking about the history of computing at the National Academies. The talk will be streamed live.

I will also be moderating a panel discussion that includes a cast of computer science all-stars: David Farber, the “grandfather of the Internet”; Robert Kahn, the co-inventor of TCP/IP and one of the “fathers of the Internet”; and Janet Abbate, the noted historian of the Internet.

Update: The videos of the Sackler Colloquium talks can now be found on Youtube.

July 28, 2013

#publications

#research

#media

My article “Is Chess the Drosophila of AI? a Social History of an Algorithm” (Social Studies of Science, 2012) was recently awarded the 2013 Maurice Daumas Prize by the International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC).

The Maurice Daumas prize is “awarded to the best submission of an article on the history of technology published in a journal or edited volume within two previous calendar years.” More information about Maurice Daumas, the pioneering and celebrated French historian of technology, can be found here for those of you who read French. A brief biography in English can be found here.

Receiving the Daumas Prize is a great honor, and I am particularly pleased to see the Chess paper, which is one of my favorite and, I believe, most historiographically innovative articles, receive some attention. The timing is also good, as an excellent new movie about chess and computers has just been released.

For the moment at least, the article is freely available from Sage. If this changes, and you do not have access to the Social Studies of Science archive, you can read draft version of the computer chess paper.

June 29, 2013

#media

Writing book reviews is one of the more important but least rewarded of all academic activities. Every professional researcher, particularly those in the humanities and social sciences, relies extensively on book reviews to keep current with a large and growing literature. As useful as they are to the scholarly community, however, academic book reviews rarely attract much attention. The exception is when the book under review is also a popular best-seller. An excerpted version of my review of George Dyson’s Turing’s Cathedral (Pantheon, 2012), originally published in the Annals of the History of Computing, has been picked up by the IEEE Computer Society.