The History of Women in Programming

February 08, 2015 #media

The public radio show Backstory devoted an entire show to the history of Women at Work. One of the segments is called Binary Coeds: The Secret History of Women in Programming and features me and my work in this area. For more on this topic, you might also check out this recent post on The Computer Boys Take Over blog.

Annals of the History of Computing

December 05, 2014 #research

As of January 1, 2015 I will be taking over as the editor-in-chief of the IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. The Annals has served as the premier journal in the history of computing for thirty-five years, and has published articles by the finest historions, computer scientists and pioneers, and industry leaders in the world.

If you are a scholar working in the history of computing or information technology, consider submitting your work to the Annals.

2015 Badash Memorial Lecture

November 15, 2014 #media

I am pleased and honored to have been invited to give the 2015 Lawrence Badash Memorial Lecture in the History of Science at the University of California Santa Barbara. I will be speaking on my recent work on the environmental history of computing. The title of the talk is The Materiality of the Virtual: A Global Environmental History of Computing from Babbage to Bitcoin. If you happen to be in Santa Barbara on January 21, 2015, please join me there!

The Computer Boys in the News

October 20, 2014 #media #research

My first book, The Computer Boys Take Over, has been attracting attention in the news recently, largely because of its discussion of gender and computer programming. This article in Fastcompany on the “Evolution of Brogramming” discusses my work in relation to the forthcoming documentary CODE: Debugging the Gender Gap. In their insightful review of sexism in the tech industry in The Baffler (entitled “The Dads of Tech”), Astra Taylor and Joanne McNeil situate my historical work in the context of recent incidents of sexism such as GamerGate.

The Cult of Masculinity in Computing

October 14, 2014 #research

Update: I titled my first book after its central characters, adopting a contemporary term for these new specialists — “the computer boys” — that for me neatly captured mixed sense of awe, mystery, suspicion, and derision with which this unexpected powerful new group of experts were regarded by their contemporaries. Like the other terms collectively applied to these experts (“wizards,” “hackers,” “gurus,” and “cowboys”) the term “computer boys” spoke to the ways in which these specialists were alternatively admired for their technical prowess and despised for their eccentric mannerisms and the disruptive potential of the technologies they developed. To many observers in this period , it seemed the “computer boys” were taking over, not just in the corporate setting, but also in government, politics, and society in general.

But there is another, more literal sense in which “the computer boys took over,” and has to do with the masculinization of computer culture that occurred over the course of the late 1950s and 1960s. It often surprises people to learn that computer programming was originally envisioned as women’s work, and that it took several decades for computing to acquire its distinctively masculine identity.

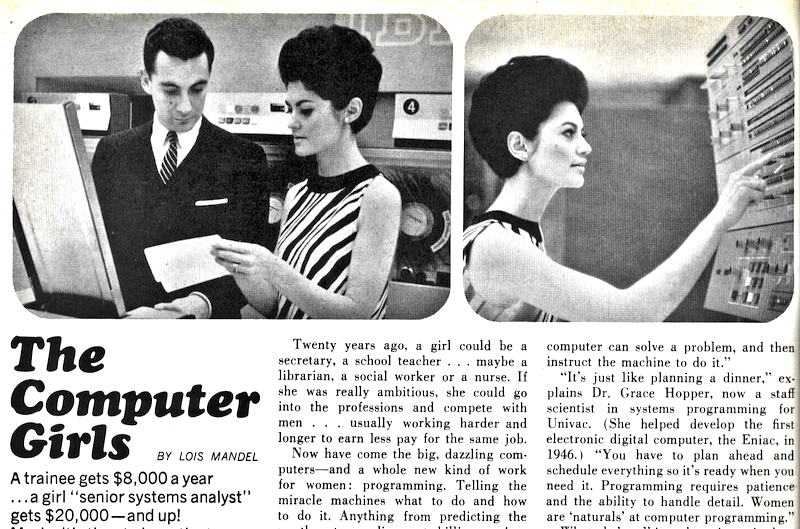

In both the Computer Boys book and a subsequent essay in the edited volume Gender Codes (which focused on the astonishing 1967 Cosmopolitan Magazine Computer Girls article pictured above) I wrote about the remarkable occupational sex-change that occurred in the history of the computer professions. I focused particularly on the ways in which the widespread use of aptitude testing and personality profiles in hiring practices in this period helped create and reinforce the stereotype of the computer programmer as young, male, and anti-social.

I now in the process of extending my history of gender and computing to cover the period between the late 1960s and early 1980s. I have a new article coming out in the forthcoming special issue of Osiris dedicated to scientific masculinities. The article is called ‘Beards, Sandals, and Other Signs of Rugged Individualism’: Masculine Culture within the Computing Professions. The focus of this piece is on the emergence of the “computer bum” in academic computer labs in the late 1970s and its subsequent popularization of this almost exclusively male phenomenon in the sensationalist media coverage of the “computer hacker” in the early 1980s.

Update: the published Osiris version of the Beards and Sandals paper is now available.

But while this new piece focuses processes of masculinization, the underlying assumption is, of course, that there is a larger history of women in computing against which these processes are revealed. It is too early to reveal much about the forthcoming Osiris paper, but in honor of Ada Lovelace day, here is one of my favorite lines from the new work:

… to borrow a relevant metaphor from computer programming itself, the presence of women in early computing was a feature, not a bug.

It is very exciting how much to see how much is happening in the history of computing in celebration of this day (and in anticipation of future celebrations), from historical documentaries on the ENIAC programmers and Grace Hopper to events aimed at encouraging women in computing.

When Good Software Goes Bad

September 20, 2014 #research #media

For the upcoming MICE (Mistakes, Ignorance, Contingency, and Error) Conference in Munich I have prepared a paper entitled “When Good Software Goes Bad: The Surprising Durability of an Ephemeral Technology.”

In theory, software is a technology that cannot be broken. Virtual gears do not require lubrication, and digital constructs never fall apart. Once a software-based system is working properly, it should continue to work in perpetuity — or at least as long as the underlying hardware platform it runs on remains intact. Any latent “bugs” that subsequently revealed in the software system are considered flaws in the original design or implementation, not the result of the wear-and-tear of daily use, and ideally could be completely eliminated by rigorous development and testing methods.

In practice, however, most software systems are in constant need of repair. Beginning in the early 1960s, large-scale computer users discovered, much to their surprise, that between 50% and 70% of all their operating expenditures were being devoted to “software maintenance.” This meant that most computer programmers were (and are) spending most of their time “fixing” other people’s computer code.

You can read a draft version of the paper here.