Chess as Drosophila awarded 2013 Maurice Daumas Prize

July 28, 2013 #publications #research #media

My article “Is Chess the Drosophila of AI? a Social History of an Algorithm” (Social Studies of Science, 2012) was recently awarded the 2013 Maurice Daumas Prize by the International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC).

The Maurice Daumas prize is “awarded to the best submission of an article on the history of technology published in a journal or edited volume within two previous calendar years.” More information about Maurice Daumas, the pioneering and celebrated French historian of technology, can be found here for those of you who read French. A brief biography in English can be found here.

Receiving the Daumas Prize is a great honor, and I am particularly pleased to see the Chess paper, which is one of my favorite and, I believe, most historiographically innovative articles, receive some attention. The timing is also good, as an excellent new movie about chess and computers has just been released.

For the moment at least, the article is freely available from Sage. If this changes, and you do not have access to the Social Studies of Science archive, you can read draft version of the computer chess paper.

Review of Turing's Cathedral

June 29, 2013 #media

Writing book reviews is one of the more important but least rewarded of all academic activities. Every professional researcher, particularly those in the humanities and social sciences, relies extensively on book reviews to keep current with a large and growing literature. As useful as they are to the scholarly community, however, academic book reviews rarely attract much attention. The exception is when the book under review is also a popular best-seller. An excerpted version of my review of George Dyson’s Turing’s Cathedral (Pantheon, 2012), originally published in the Annals of the History of Computing, has been picked up by the IEEE Computer Society.

Towards an Environmental History of Computing

May 20, 2013 #research

For the upcoming Society for the History of Technology Conference, I have been working on a paper that situates the history of computing in environmental history. This is about more than simply talking about the environmental consequences of computing (although this is an important and intellectually exciting topic), but about the role of computer technologies in structuring the relationship between humans and their natural environment. What follows is a brief synthesis of the paper. A more complete version to be posted in the future.

One of the more persistent and popular explanations of why the modern “Information Age” is so radically different from other eras in the history of technology has to do with the perceived immateriality of information technology. Whereas other technological revolutions were so clearly associated with the production of physical artifacts and the consumption of material resources, the electronic digital computer is often seen as a low-impact, environmentally-friendly, and increasingly “invisible” (or at least microscopic) technology. We all know that our cars and factories pollute, that large-scale agriculture wastes water, and that our addiction to cheap consumer goods causes landfills to overflow. Information technology, on the other hand, seems to operate largely independently of the physical environment, and in fact enables us to transcend it. To the degree that we can work, live, and interact in Cyberspace, we operate (or so we believe) independently of traditional physical or political geography.

True, the geographical and spiritual center of gravity of the computer industry, Silicon Valley, is named after a component element, but even that small recognition of the material dimensions of semiconductor manufacture manages to conveys a larger message of incorporeality: in the information economy, simple sand and intangible “bits” are transformed, as if by magic, into wealth, power, and control. The fact that Silicon Valley is also home to twenty-nine EPA Superfund sites, the largest concentration in the nation, has not managed to change the perception that the electronic computing is a “clean”, post-industrial technology.

Drawing on the literature on environmental history, this paper surveys the multiple ways in which humans, environment, and computing technology have been in interaction over the past several centuries. From Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine (a product of an increasingly global British maritime empire) to Herman Hollerith’s tabulating machine (designed to solve the problem of “seeing like a state” in the newly trans-continental American Republic) to the emergence of the ecological sciences and the modern petrochemical industry, information technologies have always been closely associated with the human desire to understand and manipulate their physical environment. More recently, humankind has started to realize the environmental impacts of information technology, including not only the toxic byproducts associated with their production, but also the polluting effects of the massive amounts of energy and water required by data centers at Google and Facebook (whose physicality is conveniently and deliberately camouflaged behind the disembodied, ethereal “cloud”).

More specifically, this paper will explore the global life-cycle of a typical laptop computer or cellphone from its material origins in rare earth element mines in post-colonial South America to its manufacture and assembly in the factory city-compounds of southern China through its transportation and distribution to retail stores and households across America and finally to its eventual disposal in the “computer graveyards” outside of Agbogbloshie, Ghana. The goal is to ground the history of information technology in the material world by focusing on the relationship between “computing power” and more traditional processes of resource extraction, exchange, management, and consumption.

My goal for the SHOT Conference over the past few years has been to explore radically new historiographical approaches to the history of computing. (See, for example, my 2012 paper on zombies and artificial intelligence) It would be hard to find a less obvious approach to the history of information technology, whose material dimensions are often dismissed as being irrelevant, than environmental history, but I think this pairing is going to prove particularly fruitful.

ACM Inroads - A call for champions

March 22, 2013 #teaching #media

The ACM journal Inroads, which is aimed at computer science educators, recently published an article on the teaching of the history of computing that discusses one of my courses. The article is entitled “A call for champions: why some history of computing courses are more successful than others” and the course that it describes — The Information Age — is one of my proudest accomplishments. When I last taught the course at the University of Pennsylvania, I had almost three hundred students. I will teach it here at Indiana University for the first time in the Spring 2014 semester. Keep your eye out!

Computer - The Information Machine

March 15, 2013 #publications

The third edition of the classic Computer: A History of the Information Machine has a cover, a website, and a publication date. When Martin Campbell-Kelly and William Aspray published the first edition of Computer in 1996, it revolutionized the discipline. Almost two decades later, it remains the most comprehensive, widely read, and influential history of computing available. This is the book that first introduced me to the discipline, and which for me is the model of how to make historical scholarship both erudite and accessible.

I am extremely proud, therefore, to have been asked by Martin and Bill to co-author the third edition. The latest version of Campbell-Kelly, Aspray, Ensmenger, and Yost includes a substantial amount of new material covering contemporary developments like Google and Facebook, but we also worked hard to incorporate the latest insights from the historical literature. The history of computing is a lively and growing discipline, and we had lots of new material to work with. Fans of the book can compare editions and play the “what is old/what is new” game. Even before I got involved with the third edition, I knew the book so well that I could usually tell…

Update: The new edition of Computer: A History of the Information Machine is now shipping on Amazon!

I400 - Information Systems and Organizational Change

January 07, 2013 #teaching

New Course

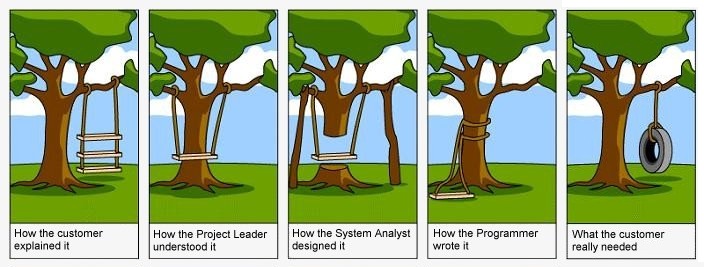

The design and construction of technology is only the beginning of the challenging process of implementing (and maintaining) complex information systems. The cartoon above, which has been floating around the computing community since at least the early 1980s, is a humorous (but accurate) illustration of the organizational dimensions of software design and development. Misunderstanding or ignoring the organizational aspects of information technology leads to disappointment, delays, cost-overruns, and often complete failure.

In this new course, we will explore the technical, sociological, ethnographic, and historical literature that deals with the organizational aspects of information technology. The focus will be on business information systems, but we will also look at scientific, governmental, and health-related organizations as well.

Download the syllabus.